Robert Leib (2016)

"The Dangers of Political Myth: Past and Present" by Robert S. Leib

Shakespeare is said to have introduced about 1000 words and over 100 idioms into the English language, and we often cite him as an immense influence on modern English as we know it. By contrast, the Nazi-Deutsch Lexicon, a dictionary of all the new words and specials senses in which old words were appropriated, lists at least twice as many introductions into the German language by Nazis as Shakespeare achieved in English.

As every voter realizes, politically motivated lies, propaganda, and spin present significant challenges to a just and fair democracy. Political myth, however, is a less recognized and potentially more dangerous adversary. While lies and propaganda might be exposed for what they are, and spin may be corrected by the ‘facts’, political myth is largely immune to argument and reason because it projects a dream for the community, a narrative in light of which a group or nation orients itself and forms its identity. At the same time, however, these myths can be used to exclude and silence those whom a community rejects. As Jewish philosopher Ernst Cassirer wrote of the Nazis’ rise to power in 1933: “The real rearmament began with the origin and rise of the political myths. The later military rearmament was only an accessory after the fact.” But, what is political myth, and how does it work? According to Cassirer, myth works according to the 'magical' function of language, a mode of speech wherein saying and being coincide. This immediate link between what is said and what becomes the case for a community means that myth can breed discontent, violence, and paralysis, even while it speaks ostensibly in terms of freedom and security, and cultural identity. “Political myth acted in the same way as a serpent that tries to paralyze its victims before attacking them," Cassirer says. "Men...were vanquished and subdued before they had realized what actually happened.” This talk examines the relationship between language and politics in the context of Nazi Germany, with an eye toward current and emerging forms of political practice.

This talk was given by Robert Leib on November 3rd, 2016 at the Peace, Justice, and Human Rights Colloquium Series at Florida Atlantic University.

¶

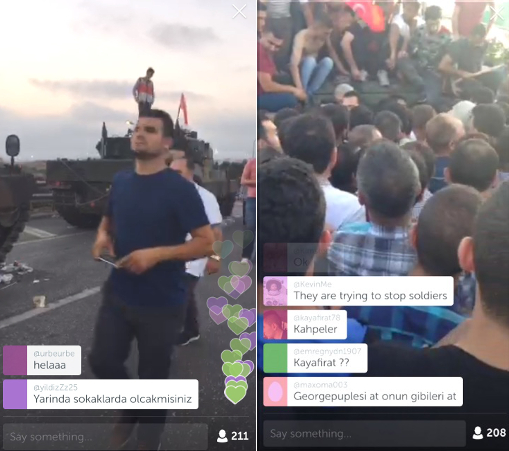

"Our Phones are Breaking (the) News; Please Don't Break Our Phones" by Lauren Guilmette and Robert Leib

This blog post engages media representations over the past week with attention to the role and the rights of citizen journalists who offered live-stream videos, images with very different frames from those offered by corporate media. But, a new patent issued to Apple this week for ‘infrared emitters’ will make it possible to shut down iPhone cameras in moments of crisis. As Julie Mastrine, author of the petition that asks Apple not to share this technology with law enforcement officials, says: "The release of this technology would have huge implications, including the censoring of political dissidents, activists, and citizens who are recording police brutality." Please read, share, and sign the petition.

Read MoreRobert Leib (2016)

"Filming on the Front Lines (in America)" by Lauren Guilmette

Against an older view of war photography that images of brutality and suffering will surely unite people of good will—“us”—against violence, Susan Sontag observes that we cannot take for granted the “we” when the subject at hand is looking at other people’s pain. This would neglect the cultural frame of interpretation—what can be depicted, which lives can be grieved, what is interesting, abject, or salacious within a given historical moment. According to Sontag, then, photographs in and of themselves cannot offer understanding of what they depict (which is the work of narrative); rather, she writes, they “do something else: they haunt us.”

Read More"Appearing Unsuspiciously: An Essay on Surveillance and Citizen Photography" by Robert S. Leib